Ferrite World

Vol. 3: Why are ferrite cores used for antenna coils?

Key Takeaways

1. Ferrite—a ceramic compound of iron oxide and other metal oxides—was invented in 1930 by Dr. Kato and Dr. Takei in Japan and became the foundation of TDK’s early success.

2. The discovery of ferrite originated from zinc-refining research and led to the first oxide powder (OP) magnets and later soft magnetic ferrite, key materials for electronic components.

3. Lodestones (magnetite, Fe₃O₄) are natural ferrite magnets formed by the Earth’s processes; ferrite technology recreated this phenomenon artificially for modern applications.

4. In the 1930s, TDK produced millions of ferrite antenna cores for “mu (μ) tuners” in radios—devices that adjusted coil inductance by sliding a ferrite rod inside to tune frequencies.

5. This innovation simplified LC circuit tuning and greatly advanced early radio technology, marking one of the first major uses of ferrite in consumer electronics.

6. The magnetic property most critical for high-frequency use is magnetic permeability—the ease with which magnetic domains align with changing fields.

7. Today, ferrite’s low loss and high permeability make it essential in automotive keyless entry, immobilizer, and TPMS antennas, allowing small coils to efficiently capture weak RF signals.

8. TDK’s high-stability ferrite materials support miniaturization, energy efficiency, and reliability in electronics spanning communication, power, and safety systems.

Lodestones are ferrite magnets produced by the Earth

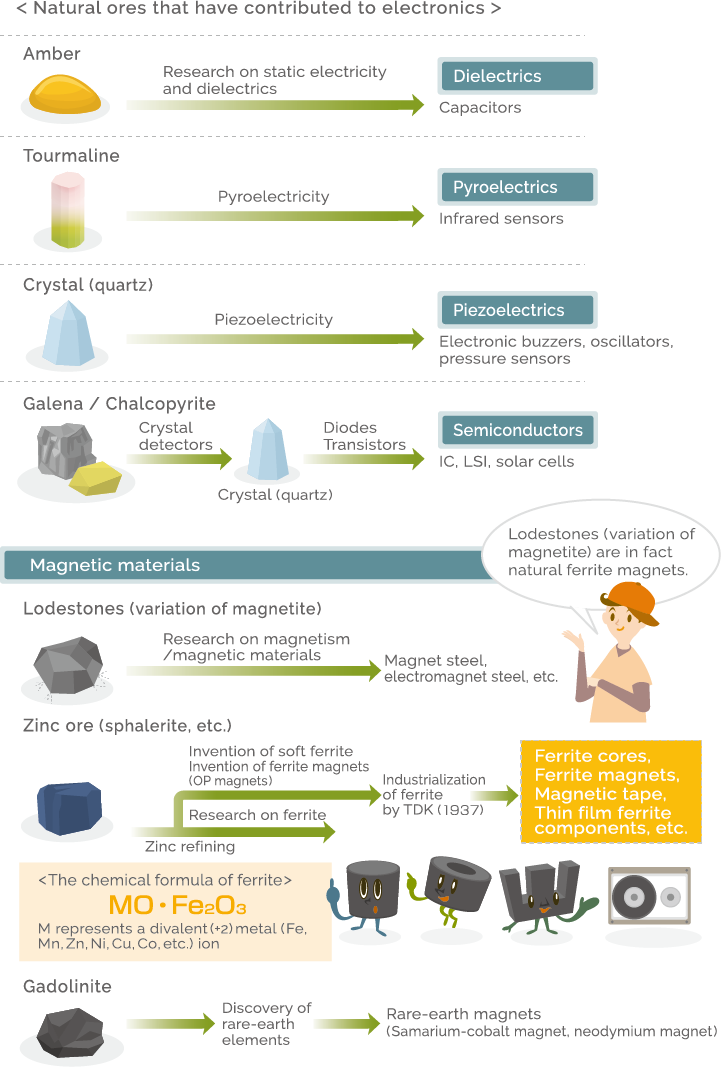

The word magnetic, the adjective form of the word magnet, means not only “of or relating to a magnet or magnetism” but also “attractive or alluring.” It was known long ago that rubbed amber attracts dust or ash (static electricity) or that a lodestone (a variation of magnetite) attracts iron. Tourmaline (electric stone), which attracts dust or ash when heated, was also called “Ceylonese Magnet” named after its locality. In the past, attraction properties were magnetic things that attracted everyone's attention.

Mineralogy greatly contributed to electromagnetism in the 19th century and also to the birth of electronics in the 20th century. The piezoelectric phenomenon, in which the application of pressure generates voltage, is used for electronic buzzers, ultrasonic transducers, pressure sensors, etc. It was first discovered by the Curie brothers in France (older brother: Jacques; younger brother: Pierre) from minerals such as tourmaline and crystal.

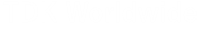

Ferrite, which was invented in 1930 by Dr. Yogoro Kato and Dr. Takeshi Takei at Tokyo Institute of Technology, is also an electronic material created from research into a method for extracting zinc from ores such as sphalerite. In order to obtain zinc, zinc ores are sintered to form zinc oxides, which are dissolved with sulfuric acid into a solution, and this is decomposed by an electric current. In this process, iron oxides contained in the ores are combined with zinc into ferrite. During a research into ferrite, which was troublesome reducing the zinc yield, it was accidentally found that there was a strongly magnetic ferrite. This is how the OP (oxide powder) magnet, the world’s first ferrite magnet, was created. Soon afterward, they also invented a soft magnetic ferrite material (soft ferrite). TDK took over the patent for it, industrialized, and sold it under the product name “oxide core” (TDK was founded in 1935, and its name then was Tokyo Kagaku Kogyo K.K.).

Ferrite is a substance represented by the chemical formula MFe2O4 or MO·Fe2O3 (M is not a specific element symbol, but an abbreviation for various metal elements), which is a compound of an oxide of a divalent metal ion (M2+) and an oxide of a trivalent iron ion (Fe3+). M is replaced by various metal elements such as cobalt, copper, manganese, and zinc, and this means that a wide variety of ferrites can be obtained. If M represents iron (Fe2+), the formula is FeO·Fe2O3, or Fe3O4, showing the composition of magnetite (Fe3O4). Lodestones which have stimulated people’s curiosity since ancient times, are in fact natural ferrite magnets. The dynamism of nature has produced natural ferrite magnets under the soil, and human technologies created artificial ferrite magnets in the 20th century.

TDK’s ferrite cores that were used in mu (μ) tuners for radios in pre-war days

German physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun, whose name was reflected in the cathode-ray tubes of TVs, made an important discovery circa 1873 that was a precursor to the invention of point-contact diodes and transistors. When measuring the electrical resistance of various minerals such as chalcopyrite and galena, he found that the resistance values varied depending on how positive and negative electrodes were applied. This resulted in a discovery of a new phenomenon, but such a principle started to be applied to crystal detectors for receiving radio waves when wireless communication started at the beginning of the 20th century.

In primitive wireless communication, dot-and-dash Morse code was sent (information was converted to short signals (dots) and long signals (dashes)) using radio waves generated during spark discharge. It was the wireless communication in which radio waves were used as a sort of smoke signal. Receivers had more technical difficulties than transmitters. Radio waves received by an antenna flow through circuits as alternating current. If, for example, an ammeter is used to detect these by the swinging of the needle, alternating current, which flows back and forth, does not cause the needle to swing. Therefore, a rectifier to obtain only one-way current from alternating current is required. This is called a wave detector.

While various types of wave detectors were devised, a crystal detector was widely used because of its simple mechanism. The electrode needle is applied to a surface of natural ore such as galena and chalcopyrite, and the most sensitive position is found manually. This is the same principle as that of diodes, which pass current in only one direction.

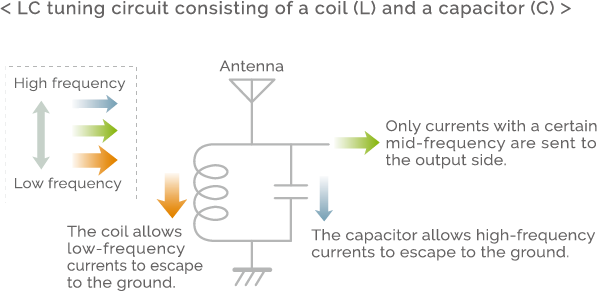

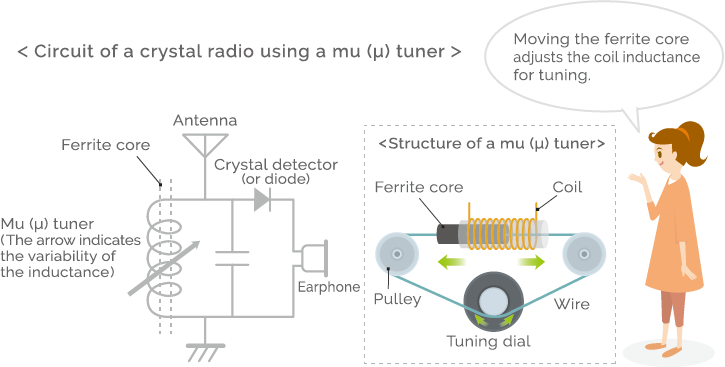

In the 1920s, when radio broadcasting started, crystal detectors were also used in radio receivers. These are so-called crystal radios. In order to receive radio broadcast, it is necessary to tune the radio to the frequency of radio waves transmitted. To achieve this, an LC tuning circuit consisting of a capacitor and a coil was used. There are two types of LC tuning circuits: those that can change the capacitance of the capacitor (C) and those that can change the inductance of the coil (L) (the number of magnetic field lines generated by the coil). The figure below shows a mu (μ) tuner using a ferrite core. Inserting the ferrite core into the coil collects many magnetic field lines, and moving the ferrite core inside the coil changes the inductance to tune the radio to the frequency of broadcast radio waves.

The 1930s saw the growth of high-frequency technologies. About 5 million units of TDK’s ferrite cores were manufactured as antenna cores for radio receivers or wireless communication devices until the end of the Second World War (1945). TDK Museum (Nikaho City, Akita Pref.) houses many precious products that help trace the developmental history of electronics, including a radio using a mu tuner in pre-war days.

Ferrite cores utilized in automotive keyless entry systems

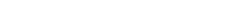

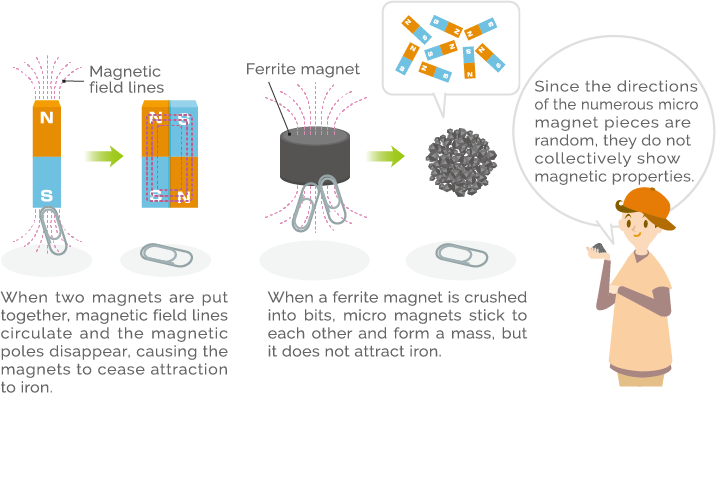

When two bar magnets are put together with the opposite magnetic poles facing each other, they cease to attract iron. This is because magnetic field lines start to circulate inside the magnets and the magnetic poles cease to appear outside them. When a ferrite magnet is crushed into pieces, each of them becomes a micro magnet and sticks to each other and together form a ball. The ball-shaped ferrite magnet does not attract iron either. This is also because many micro magnets stick to each other in random directions.

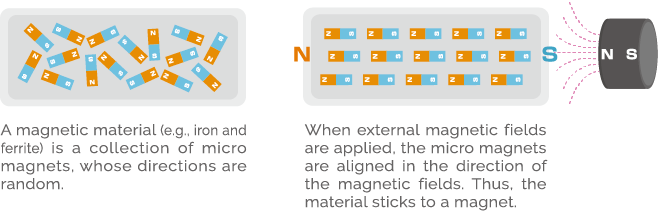

This can be used as a model to help easily understand the reason why magnetic materials such as iron and ferrite stick to a magnet. A magnetic material such as iron and ferrite consists of numerous micro magnets, but normally the directions of their magnetic poles are random (a circulating structure of magnetic field lines is formed). Therefore, iron does not attract iron, and ferrite does not attract ferrite. However, if magnetic fields are applied externally, the randomly placed micro magnets are aligned in the direction of the magnetic fields. Then, they collectively behave like a single magnet, and stick to an external magnet.

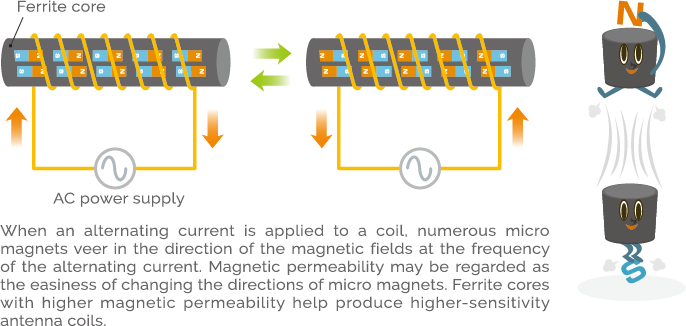

If alternating-current magnetic fields are applied to a magnetic material, the direction of the micro magnets is reversed each time the direction of the magnetic fields changes. The easiness of initiation of this reversal is called magnetic permeability, and is a very important characteristic in a kilohertz, megahertz, or higher-frequency range. For example, an automotive keyless entry system is a system to open and close the doors or start the engine through exchange of radio waves between the key and the vehicle without inserting the key. The key incorporates a small antenna coil called a transponder coil. In the coil, a low-loss, high-magnetic-permeability ferrite core is used that is stable against thermal fluctuation. The system can receive weak radio waves and can be used for several years without battery replacement because a small but high-performance ferrite core is used.

A transponder coil is also used in automotive immobilizers (antitheft systems), tire pressure monitoring systems, etc. Ferrite materials are utilized for various purposes including not only miniaturization or energy-saving of electronic devices, but also safety, comfort, and security.

Conclusion

From the Earth’s natural lodestones to the engineered ferrite cores powering wireless keys and sensors, ferrite’s journey spans centuries of discovery and innovation. TDK transformed this mineral curiosity into a cornerstone of modern electronics—first in radio tuners and now in every field where magnetic control meets high-frequency precision. With its unique balance of stability, permeability, and low loss, ferrite remains a quiet enabler of connectivity, safety, and miniaturization across today’s electronic world.

FAQ

What is ferrite made of?

Ferrite is a ceramic compound of divalent metal oxides (such as Mn, Zn, Ni) and trivalent iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), expressed as MFe₂O₄. Its composition determines whether it behaves as a hard (permanent) or soft (inductive) magnetic material.

How was ferrite discovered?

While researching zinc extraction, scientists found a byproduct that exhibited strong magnetism. This accidental discovery became the basis for synthetic ferrite and led to TDK’s founding in 1935.

Why is ferrite used in radio antenna coils?

Inserting a ferrite core into a coil concentrates magnetic field lines, increasing inductance and allowing smoother, more compact frequency tuning—critical in early radios and modern wireless circuits.

What was a “mu (μ) tuner”?

A pre-war tuning mechanism that varied coil inductance by moving a ferrite rod within the coil, enabling precise frequency selection in LC circuits.

What does magnetic permeability mean?

It’s the measure of how easily magnetic domains within a material align with an external magnetic field. High-permeability materials like ferrite enhance coil performance, especially at high frequencies.

How are ferrite cores used in modern cars?

They’re embedded in transponder coils for keyless entry, immobilizers, and tire-pressure sensors—capturing low-frequency communication signals while maintaining thermal and magnetic stability.

Why don’t ferrite particles or magnets always attract each other?

In unmagnetized form, the internal magnetic domains point randomly, canceling overall magnetism. Only when aligned by an external magnetic field do they behave as a single magnet.

TDK is a comprehensive electronic components manufacturer leading the world in magnetic technology